A common psychological metaphor: the best way to stop a tug of war is to put down your end of the rope.

Whether someone’s at the other end, or it’s an immovable challenge, there are times when the best thing to do is to consciously drop the rope.

A common psychological metaphor: the best way to stop a tug of war is to put down your end of the rope.

Whether someone’s at the other end, or it’s an immovable challenge, there are times when the best thing to do is to consciously drop the rope.

From the prologue of This American Life, Episode 178.

Ira Glass: “When we were weak we told ourselves we were strong. And sometimes — if we were very weak — we told ourselves we were very, very strong.”

We are often fortune tellers. Not because of premonitions, self-fulfilling prophecies, or foregone conclusions. But because we invent the world we see in our minds. We lean into who we tell ourselves we are.

When we speak of defeat, we draw it to ourselves.

And when we speak of strength and resilience, we become them.

It’s not that the air is stagnant. It’s just that we’re moving too fast.

Sometimes, to feel the delicate breeze, we have to sit very, very still.

And sitting still runs counter to our usual stimuli.

Rather, sitting still while undistracted — being fully present — is not our usual mode.

But it’s a worthwhile practice.

There is, after all, the delicate breeze that awaits us.

“Excuse me. Would we be able to use your electricity, please? I have a 100-foot extension cord.”

The person setting up the public address system for a street fair in our town was asking for help. (We were happy to give access to a receptacle.)

One thing I like about this interaction is that the requestor was making it easy for us to help. He knew he would need electricity that day. Instead of showing up with empty hands, he brought along something that made the assist effortless.

* * *

Arriving prepared doesn’t always mean bringing everything you need; sometimes it means you’ve considered the conduits through which others can be helpful.

When you make helping easy, you’ll find help often.

To properly close the side gate in our yard, you need to lift the handle an inch.

This is how the hardware has worked for ten years. (We don’t use this entrance often.)

I had become so used to lifting the gate that I never considered aligning the hardware.

Yesterday, I removed the latch mechanism and reinstalled it … an inch lower.

With two minutes’ effort, everything now works swimmingly.

From time to time (or maybe all the time) it’s good to look around to see where we can reduce friction, where we can create alignment, and where we can help things to work as they should.

It might not take much time or effort to make a change that has lasting impact.

Some problems are sticky. Not because we’re lacking all ability, but because we don’t know which ability to amplify. We don’t know which muscle to flex or which skill to develop.

And so some problems can feel insurmountable.

In a way, one of the best skills we can develop is the mental skill of understanding problems and recognizing potential deficiencies.

When we gain these insights, we learn where to focus our efforts.

How do you measure up against the average?

Hold that thought.

When you buy a shoe, do you ask for the average size? Probably not.

Averages can be useful. In some domains, the average can be a benchmark.

But don’t be fooled. What propels you forward (in the things that matter) is unlikely to be related to how you measure against the average.

Painting isn’t obsolete because of photography. But it has changed.

Handwriting isn’t obsolete because of the Gutenberg press. But it has changed.

Furniture-making isn’t obsolete because of IKEA. But it has changed.

Art-making isn’t obsolete because of artificial intelligence. But it’s changing.

More and more, we’re only limited by our imagination, not our physical skill and dexterity. New tools are being invented every day. The latency between ideation and creation is ever shrinking.

So our task is not to fight it, but to recognize it and to understand its implications in the work we do. To honestly ask, “What’s the value of doing this the old way when it can be done in this new way?”

We don’t have to embrace every new thing and we don’t have to cling to tradition.

Instead, we can work to understand our options — all of them — and we can make informed choices.

We tried to save the bird.

We couldn’t.

My older son found it standing, unmoving, in the middle of the road. It must have fallen from its nest.

It perched on my finger as I carried it to a nearby tree where we hoped it could rest and heal.

But within a few minutes, it became clear that the little fellow wasn’t going to make it.

For a moment, I thought to shield my boys from this trauma. I could remove the bird and let them think it flew away.

But I knew better.

Death is a natural part of our world. We can’t hide from it.

My younger son was the most curious about the creature. I explained what was happening.

He cried.

We sat together quietly.

He asked if we could bury the bird if it died, and we did.

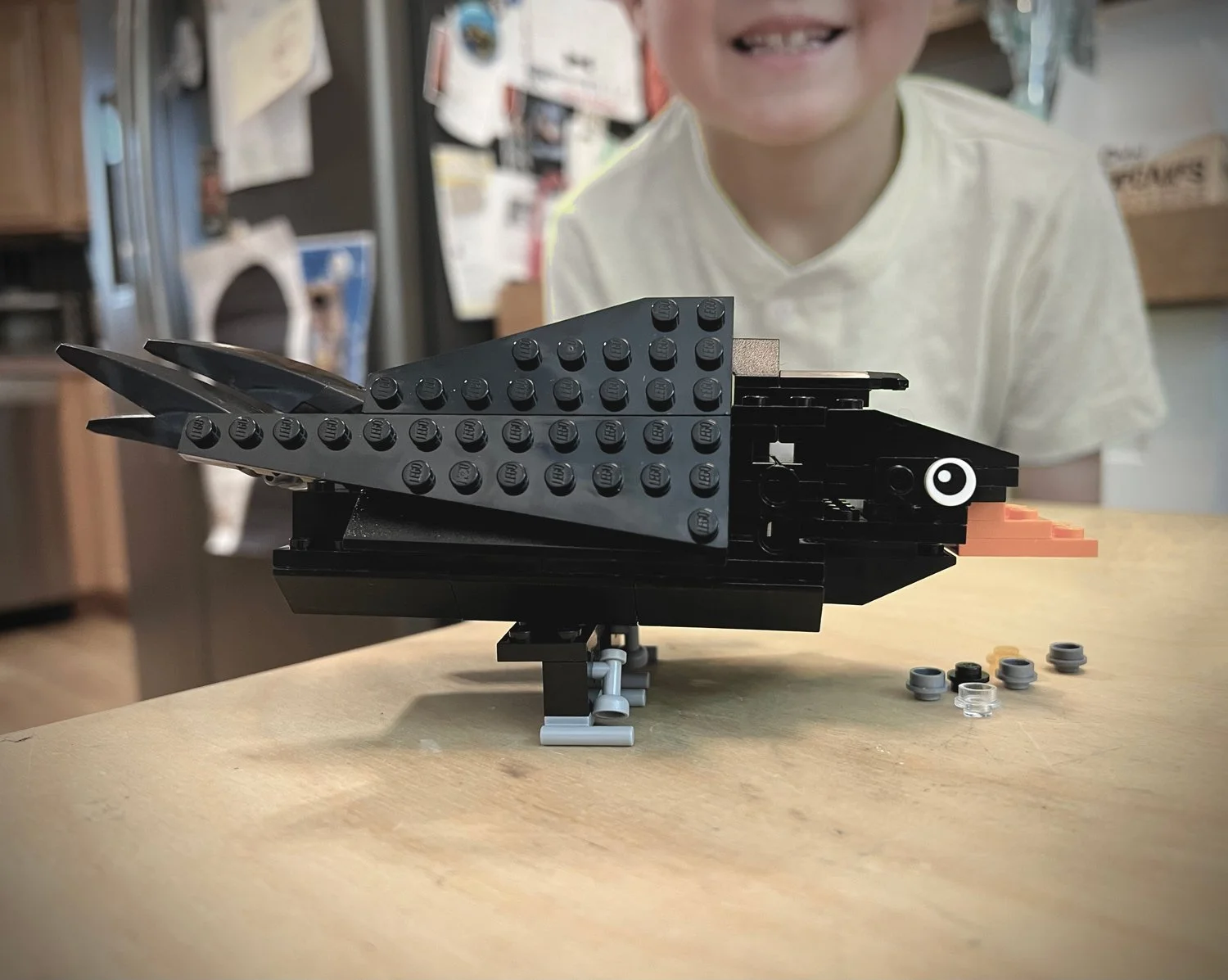

Later that day, my son asked me to come to his room to look at something.

He had recreated the bird using LEGOs. A memorial. It even had a limp left wing, just like the one we found.

Death. Mourning. Remembrance. Celebration.

It all comes in sequence. We can hide from the difficulties nature offers, but then we’re hiding from the learning and growth too. When we accept the natural way of things, we can find ways to create beauty.

From grief, creativity. From death, new life.

Waiting for inspiration is a trap.

We show up and do the work whether or not we feel inspired. That’s part of the practice.

But when inspiration does present itself — like an unexpected state of flow — you hold onto it. Not casually, but intentionally … with white knuckles like you’re headed into a turn on a roller coaster.

We’re not always inspired. But sometimes, inspiration arrives as a timely gift. Ride it where it takes you.

What have you been doing while no one is looking?

We are our habits. And many of our habits are personal. Private.

But over time, what we do repeatedly — even if no one sees — will begin to show on the surface.

How we take care of ourselves, what we choose to learn, how we relax, what we consume, what we practice … all of these habits coalesce like an emergent pattern.

As the evidence of your own habits begins to show, what will we see?

A picture is worth a thousand words. Some of them might even be true.

* * *

We know that pictures aren’t reality. Pictures can, at times, capture a version of reality. But they can also tell stories that are entirely invented.

More and more, it’s difficult to know which is which.

What we do know, however, is that the feelings images evoke — those can be quite real. Pictures can cause us to be deeply moved, and to take real action.

As we traverse unprecedented shifts in technology and visual generation — where algorithms and artifice abound — keeping a knowing connection to our own perceptions and experiences … that seems quite important.

In the hours just after midnight, it was the wind through the trees. As the sun rose, birdsong. Later, the business of commuting. People moving about. Traffic. Tools and equipment. In the afternoon, laughter. Children playing. Neighbors talking. And it all tapered once again in the evening.

Our soundscape cycles and changes in an ongoing rhythm.

If you’re not hearing what you want to hear — what you need to hear — perhaps you’re just listening at the wrong times.

In a world that encourages us to be physically sated — through thoughtful diet or overindulgence — let that not be our creative goal.

Instead, aim to stay hungry. To stay curious. To stay working.

In your creative life, don’t seek fullness. Seek the the mid-meal feeling of, “This is delicious. More, please.”

Our appetite for creativity and curiosity isn’t a task to eliminate. It’s a state to maintain.

Yesterday, I witnessed two adults reconcile.

They had recently argued about an organizational policy, and the argument didn’t go well.

And here they were, days later, having a calm discussion. Finding a way forward.

Afterwards, they’d go their separate ways having come to a place of peace.

It was a fine example of conflict resolution.

Too often, one disagreement leads to another, words are exchanged, and bitter rivalries develop. People choose sides. It gets messy.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

We can do better … and some are leading by example.

Sometimes our plans go off the rails. Despite our best efforts, things fall apart.

It’s helpful to keep in mind that the in-progress derailment is a poor time for self-flagellation.

Your inner critic will disagree. The inner critic is quick to speak up. Quick to point out that you’ve broken into a sweat. Quick to highlight the royal mess you’re making.

But in those moments, critique isn’t what’s needed. Calm is what’s needed.

Let the thought be, “For now, I’ll get through this as best I can.”

Mentally note areas where you can learn, but don’t dwell on them.

Silence the critic and rouse the inner coach. Even the inner cheerleader.

And recall that you learn precious little from a smooth ride; you learn a lot when things come off the rails.

In sport, an assist is generally an action taken by one player that results in another player scoring. For team efforts — in the field, on the court, or at the workplace — assists are critical.

It’s possible, too (without being selfish) to set yourself up with an assist.

You can plan in a way that reduces friction toward your goals for tomorrow. You can keep your belongings organized so when you need them, there they are. You can try to anticipate unusual scenarios so that if they arise, you’re prepared.

It’s a way of thinking about tomorrow-you getting an assist from today-you.

* * *

At this moment, are you benefiting from a self-assist? Surely in some ways.

And if not, you can change the pattern moving forward.

Many times, the problem is not that we’re at a loss for ideas.

No. Often, the problem is that we’re amidst countless, partially formed ideas. Like we’re trying to capture a single raindrop in a storm.

But solutions don’t come from grasping at raindrops. They’re drawn from the reservoirs.

So let the rain fall. Have patience. Most ideas don’t arrive fully formed. But trust that they do come together, little by little, sometimes drop by drop.

They say that nature abhors a vacuum.

Perhaps this is why clearing and holding space can be so useful in a creative practice.

When we thoughtfully create voids and emptiness, we prompt opportunities for creation. These gaps become primers for possibility.

A fresh canvas. A blank day on the calendar. A period of silence. A clean studio. These are all vacuums in their own way, all in service of creativity.

What might flow inward in the space you create?

Completing the lessons doesn’t mean you stop practicing the skills.

Lessons are a beginning.

The practice is ongoing.

* * *

We’re lifelong learners; practicing is a continuous part of that journey.